Artist Kaye Blegvad’s Illustrations Will Make Anyone Struggling With a Mental Health Issue Feel Totally Understood

Ladies First highlights women and girls who are making the world better for the rest of us.

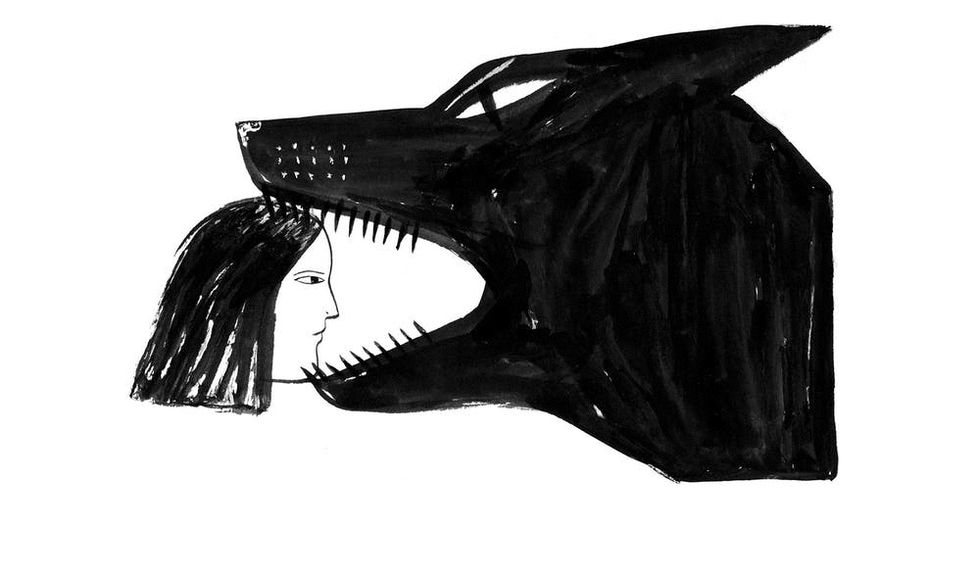

Brooklyn illustrator Kaye Blegvad says that living with depression is like owning a bad dog. It’s an old metaphor but Blegvad uses it in a unique way: to make it easier to understand the ways that depression (and other mental health issues) can affect both the people who are wrestling with it, as well as friends and family who might have trouble imagining what it’s like to experience it. Her most recent project is Dog Years: An Illustrated Book About Mental Health, which she explains “is a book about living with that dog, training it, and learning to make peace with it.”

The illustrations are from a visual essay Blegvad created to mark Mental Health Week in October, and were originally published on Buzzfeed. Now she’s turning her essay into a beautiful, printed book — because holding art in your hands is much nicer than staring at it on a screen. (Her Kickstarter campaign runs until December 7 if you want to get your hands on a copy of the book before everyone else does.)

We talked to Blegvad about how depression has shaped, informed, and sometimes gotten in the way of her work and how, with time and effort, she’s learned to keep her “dog” leashed.

B+C: On your Kickstarter page you write that you hope this project will make it easier for people to openly discuss depression. Can you talk a bit about your own experience with trying to explain to friends and family what it’s like to live with that particular mental health issue in a way that made you feel like they really understood you?

Kaye Blegvad: It’s still a work in progress, to be honest! I’ve found people understand in pretty varied ways. I’m lucky that my parents understood pretty fast — there’s depression in my family so they both had experience with it. And most of my friends have been pretty understanding. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy to understand the specific ways it affects me, or easy to accept the specific ways it makes me behave. Depression really sucks up energy and sometimes makes it feel frightening and overwhelming to reply to a text or leave the house. That means I’ve often been a pretty absent friend, and that’s a lot for people to put up with. I’m working really hard on it and I do feel really fortunate that the older I get, the more my friends understand what’s going on.

B+C: The book you’re making takes the idea of depression and anthropomorphizes it as a dog, something that exists outside the person who’s experiencing depression. How does it help to mentally separate it that way?

KB: I think it is helpful to give yourself a little distance — to be able to see it for what it is, away from your feelings about yourself. It lets you see how it truly affects you, and I think it also makes it easier to share with others. It becomes less about you and so there’s less pressure to just “get over it” or “snap out of it.” I’ve found it helps me to accept it too — it’s here, this thing that is a constant companion, and somehow I’m more able to feel at peace with that if I think of it as slightly separate. If it’s just a part of myself, then I spend a lot of energy fighting it and chastising myself for allowing it to exist.

B+C: The metaphor of the black dog [to describe depression] is really interesting and has some history to it. You point out that Winston Churchill used it and writer John Bentley Mays also used it in his memoir about depression, In the Jaws of the Black Dog. That title especially makes depression sound like a huge, fearsome thing — but that’s not the way you’ve illustrated it. Your dog is a normal, average black dog. Why did you decide to draw it that way, as opposed to some oversized beast?

KB: I think the black dog can be a bit of a shapeshifter. It has moments where it towers over you, and moments where it’s just a little pup at your heels. But on the whole, I like thinking of it as just a regular dog. I guess it helps normalize it. It’s not a supernatural beast that you have no power over. It’s a dog that you can manage and train. You are bigger than it, and you’re the boss — you’ve just got to figure out what it needs to calm down.

B+C: In his memoir, Mays wrote that his work as a writer was often interrupted or put on hold because of his depression. Of course, it’s not only creative pursuits that can be halted by mental health issues, but I’m wondering how depression has affected your work as an artist and if, along with the negatives, there have been positives too?

KB: Depression has had a large effect on my work — both the contents of my work and on my ability to make work at all. I lose a lot of days to it. Less now than I used to, but it’s still not unusual to have a few days a month where I can’t work. It’s tough. Sometimes I think about all the things I could have done if I hadn’t lost those days, and there’s a real feeling of loss. The dog ate a lot of my life. But I do think there’s something to be said for the work that you do in spite of that.

I don’t have a ton of time for the “tortured artist inspired by madness” trope, but there is a real therapy in working, and it can be an extremely valuable respite. I have used work to process pain, to exorcise demons, to understand what’s happening, to escape. I do think that knowing how easy it is to lose days to depression motivates me to maximize the days I can. I work fairly obsessively and don’t like to stop when I’m on a roll. It feels like a race to beat the clock. I’d also like to think that having experienced some of that darkness has made my work a bit deeper, more meaningful. I try not to make throwaway things. Surviving gives you more stories to tell.

Have you found your own creative way to talk about mental health? Tell us about it on Twitter!

(Images via Kaye Blegvad)