Everything I Need to Know, I Learned from Missy Elliott

The year 1997 was all about the music video. MTV, VH1, BET, and The Box played them almost exclusively. Like every other 12-year-old coming of age during this sweet spot in pop culture history, I consumed them all voraciously.

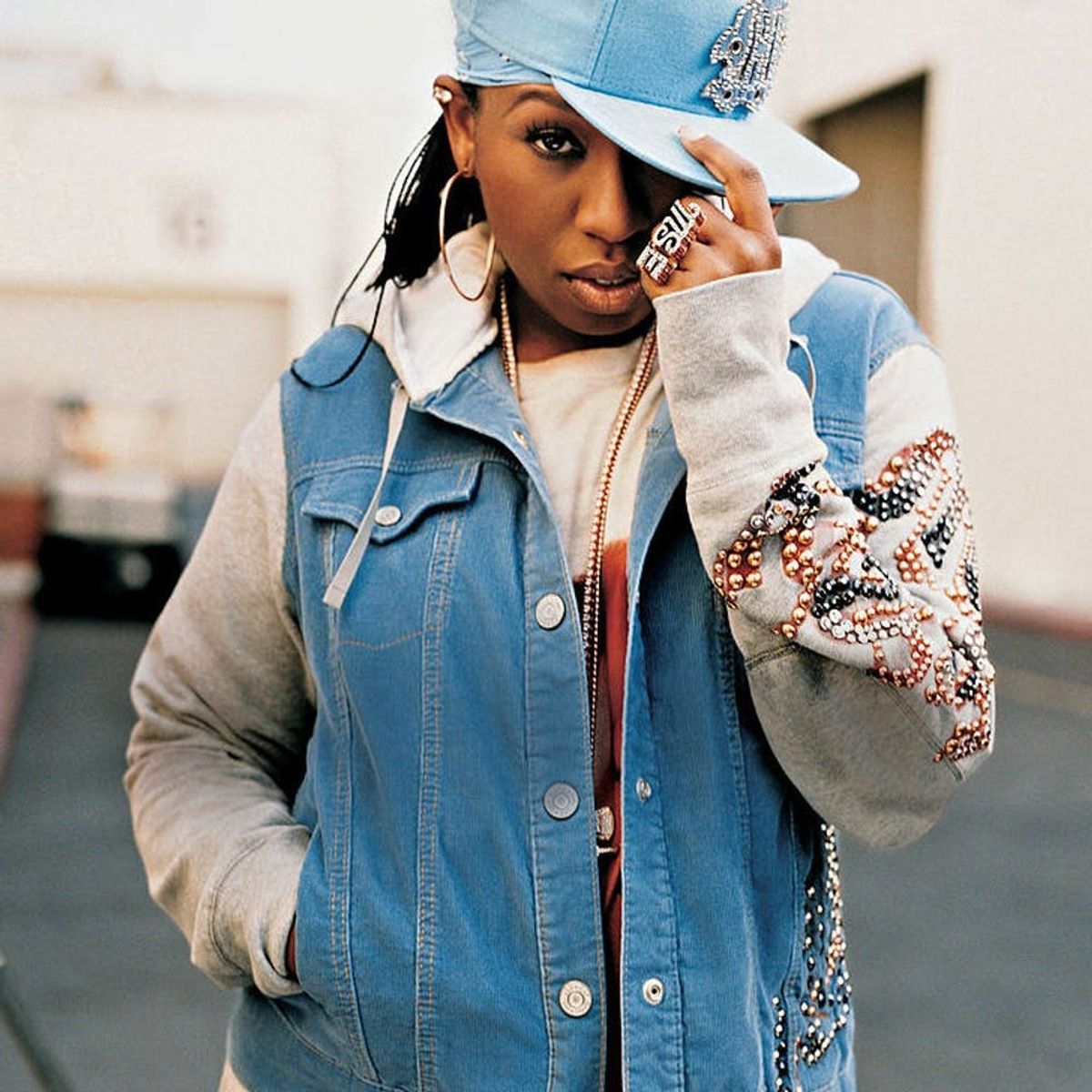

Before reality shows littered the landscape, every dance move, outfit, and lyric in music videos was studied, dissected, discussed, and mimicked among friends at school. Then, in that fray of boy bands and thin, young pop starlets, Missy Elliott exploded onto the scene.

I held my breath for the entire three minutes and 59 seconds of her first music video, “The Rain.” A black woman wearing a trash bag and rapping about being super duper fly, interspersed with shots of her driving around in a Jeep with a head full of short finger waves. I had never seen anything like this before on TV.

As a young, fat, black girl, this was like the vision of Jesus in a piece of breakfast toast — unexpected and life- changing. Before Missy came along, there were male rappers, and there were thin sex symbols like Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown. While I loved them all, I couldn’t always relate to their passion for designer handbags, their perfectly styled hair and makeup, or their skin-tight outfits. Missy opened the door to more diversity, to short hair, to wild outfits that weren’t hyper-revealing, and plus-size beauty in all its supa dupa fly glory.

I couldn’t ask for more than the first single; but then came her second single. “Sock It 2 Me,” featuring Da Brat — another performer who bucked gender-related expectations — was a more than a song; it was a lesson in sisterhood and self-love. Here were two non-stereotypical female artists joining forces for a song about owning their sexuality. It was a revelation.

Prior to Missy, I wasn’t the most confident kid in school. I developed early, and though I looked more like a woman than most of my classmates, I was most comfortable in the role of “tomboy.” That combination made navigating my new body less than ideal. It didn’t help that my hair was thicker and coarser than other girls’ in my class and that, unlike them, I preferred jeans and track pants to trendy, frilly clothes. I knew I was different, but it wasn’t empowering. It was isolating.

But then came Missy, rocking her Kangol hat and Adidas, feeling comfortable in her own skin. She made me feel more comfortable in mine. For so long I’d struggled with my identity, trying to dress more “girly” even though it didn’t suit me, trying to will my body to meet some narrow feminine ideal. Finally, I could just be myself. I was compelled — watching Missy flawlessly and unapologetically embrace her talent, her sexuality, her body, and her wild style — to do the same.

Over the years Missy continued to prove her staying power, constantly reinventing herself musically (see her collaborations with Timbaland and the late Aaliyah), while still staying true to her beliefs, specifically when it came to sex. “Get Your Freak On” and “One Minute Man” flipped the script on slut-shaming, reframing sex as something women enjoyed as much as men. Meanwhile, “HotBoyz” kicked off with a lesson in self-respect (What’s your name, ’cause I’m impressed/Can you treat me good, I won’t settle for less).

“Work It” took the vibe to a whole new level. Missy’s lyrics were purposely sexually explicit. She was basically saying that women didn’t have to rely on euphemism and metaphor to express what they wanted. They could be just as direct as men, even when it came to making the first move. (Gimme all your numbers/So I could phone you.)

Growing up in a society that often suggests fat women generally — and fat, black women specifically — should be grateful and compliant in all things love and sex, Missy’s message was enlightening.

This summer, she’ll be returning to the concert scene for FYF Fest in Los Angeles. I still marvel at the comeback she staged during the 2015 Super Bowl show, introducing a new generation of young women to her brand of empowerment.

I know somewhere there is a 12-year-old girl who doesn’t see herself represented. Maybe she’s a bit quirky and loves to dance, or feels somehow different from her classmates. Maybe she hasn’t yet learned how to express herself. Maybe she hears “I’m Better” on her phone while she’s walking to school.

It’s another day, another chance/I wake up, I wanna dance.

Maybe she’ll figure it out.

Porscha Coleman is a Washington, DC area-based writer focusing on intersections of identity (race, gender, class) and popular culture.

Got a story you’d like to share with our readers? Send your pitches and/or unpublished essays along with a brief bio to pitch@brit.co.

(Photos via Vince Bucci/The Gap/Getty)